|

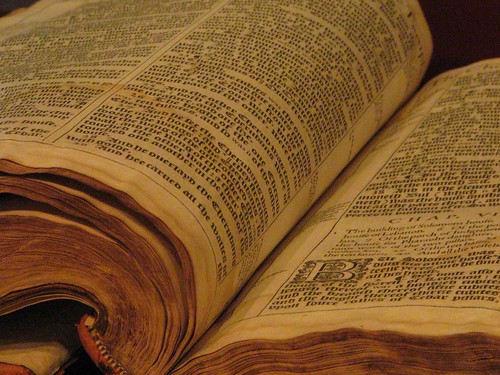

| Photo by Bookchen |

As I suggested in my post on Friday about various biblical translations, the King James Version of the Bible

Before the spirit of the Renaissance came to England, bibles in the vernacular were almost completely unavailable. Most preachers used Latin translations. Only in 1583 was the first complete English translation available. When the King James Version was published in 1611, it was printed in gothic-looking "Black Letter" font on thick folio pages, 11 inches by 16 inches. This edition, arriving in a world of newly-expanding literacy and love of literature (as can be seen by the success of Shakespeare and Donne), was a sensation in the world of books. The translation's traditional and poetic language alienated some readers and listeners, but its style also assured that the translation would be of lasting value.

The King James Bible was also born into a world of religious conflict. The Church of England was at war ideologically with Puritan churches. There were disagreements among the members of different sects about Biblical interpretation and translation. King James I proposed the creation of a version which could unite the groups. He assembled a group of scholars with a variety of viewpoints and charged them to work together to produce a translations both sides could accept. Marginal notes and interpretations were removed from the final text, since they had the potential to create conflict on either side. James I's official endorsement of this translation underlined the king's authority as the head of both church and state, increasing his own claims to power.

Campbell's study carefully traces the history of the King James translation across time and place. I find his chapter on the history of the King James Version in America to be especially fascinating. Pointing out that America now has one of the highest rates of church attendance in the world (while Europe has become increasingly secular), Campbell suggests that "the centre of gravity of the King James Version (KJV) has gradually moved across the Atlantic." Although other translations are often used in the States, Campbell argues that the KJV has a special place nonetheless. The chapter explores the version's impact in this country from the earliest days (when British embargoes encouraged American colonists to prepare their own editions) through the inauguration of Barack Obama.

Although one does not expect a history of the Bible to cause one to laugh aloud, I found myself not only giggling throughout but wanting to read aloud to my family all the funny bits. I was especially amused while reading Campbell's catalog of typos and other errata in the early editions of the King James version. (He acknowledges that one or two examples were perhaps sabotage rather than pure errata.) One edition of the King James made adultery compulsory by omitting the word not in the Ten Commandments: "Thou shalt commit adultery." Another version featured this adjustment of a verse from 1 Corinthians: "Know ye not that the unrighteous shall inherit the kingdom of God?" And the people who set the text must have been feeling especially guilty when they recast one psalm to say that printers (rather than princes) "have persecuted me without cause." And the stories continue. Errata led to the Wicked Bible, the Murderer's Bible, and even a very sour Bible, where instead of grapes being turned into wine, the word vineyard is turned into vinegar.

Although laugh-out-loud anecdotes play only a small part in the book, Campbell's style is consistently smart and witty whether the author is making lighthearted remarks about pub lunches or referring us to websites selling t-shirts with the words "Real Men Use a King James Version Bible." Academics will appreciate his scholarly rigor while more casual readers will find his book understandable and appealing.

The KJV has had an enormous impact on our current language. Often we are complete unaware of the book's echos in our daily speech. "When people are said to be 'at their wits' end,' for example, there is no awareness of the source of the phrase in Psalm 107:27," explains Campbell. "Similarly, an escape by 'the skin of my teeth' no longer evokes Psalm 19:20" and "the 'salt of the earth' no longer recalls the words of Jesus at Matthew 5:13". Even phrases like 'the writing on the wall,' 'the fly in the ointment,' and 'you can't take it with you' come from the text of this Bible. Campbell points out that while many of these phrases were not new to the King James translation, it nevertheless served as "a conduit through which many phrases in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century English have survived up to the present."

In addition to these and other particular phrases, we imitate both the formal archaic language and the distinctive rhythms of the King James in our efforts to create solemnity and a sense of wisdom. We do this even when we do not intend to be religious. I will explore this theme of the linguistic continuity of the King James translation more tomorrow when I review David Crystal's Begat: The King James Bible and the English Language

In the end, Gordon Campbell argues that the linguistic importance of the King James version has been far less relevant than its emotional impact. "It is the King James Version that has been loved by generations of those who have listened to it or read it to themselves or to others," says the author. "Other translations may engage the mind, but the King James Version is the Bible of the heart."

* * *

Thank you very much to Oxford University Press for sharing with me a copy of this important book.

Note: In addition to his history of the King James version, Campbell, a professor of Renaissance Studies at Leicester University, has prepared a special anniversary edition of the King James Bible

No comments:

Post a Comment