Reading about Amanda and Jason’s family book club was an inspiration to create our own. We’ve structured our book club a bit differently because of the age of our child, the size of our family, and our personal interests and needs. Because A. is reading some emotionally complex books for his banned book club at our local library, we had already been thinking of reading a few of the texts as a family in order to talk about the difficult issues. So this month, we decided to discuss F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby

* * *

My son and I had a bit of discussion before David joined. Listen in for a moment:

Me: What did you think of this book? Did you enjoy reading it?

A: Yes, I did. Absolutely, old sport. I thought it was very interesting how Fitzgerald provokes thoughts in his readers. I'd never really read books where I saw major symbolism before, and that was a new experience for me.

Me: Can you talk about some of the symbols you saw and what you thought about them?

A: The green light at the end of the dock! I think someone at one of Papa's meetings used the same idea recently. It seems to be referring to the quest for the American dream. Another one of my favorite symbols is the eyes of Dr. T.J. Eckleburg. There are a lot of ways to interpret it. In my book group, someone said it could be the watchful eye of God.

Me: What do you think of the eyes on the cover? I've heard that many editions of the book use this picture and that Fitzgerald knew the illustration before he completed his novel.

A: Well, they could definitely be referencing the doctor's eyes. Because of the lips on the face, it seems like they may be a woman's eyes--maybe Daisy's. The figure is crying. It is kind of funny that the tears look like an exclamation point. The tears also look kind of like Long Island where the story takes place. At the bottom, a city seems to be portrayed. The bright lights show there is a lot of excitement there.

Me: Interesting! I thought it was a fairground. It made me think of the line in the book when Gatsby wants to go to Coney Island, in his car, late one night. I like your idea that it shows excitement, the high life.

A: Is there anything you see in the book now that is different from the way you read it when you were in ninth grade?

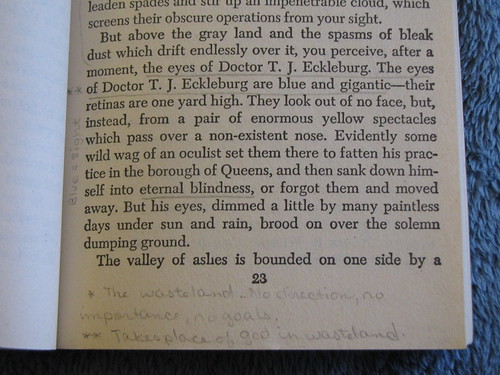

Ah, yes--I read this book many years ago. And I still have that 9th grade book, full of my notes and underlinings. The doctor's eyes drew my own attention back then:

See that round early-teen-girl handwriting? Yikes. Still--it is much more legible than my writing these days. Who knows what I will make of my book notes in another thirty years.

(Comment at the bottom of the page: the billboard with the picture of the eyes "takes place of god in wasteland." )

I think the biggest change in my understanding of the book now is that I struggle more with Gatsby's relationship with Daisy. Does he love her? Did he ever love her? I used to be sure he did when he was young, and sure as an adult he was trying to get back that love. Now I feel more that he wants to win her to prove that he has reached success in his life. She seems to me no more than a trophy representing the rich life--one who speaks with the voice of money and can be collected just as easily. My partner David does not get this impression at all, and I think my son is a little young for any real insight on this question. Any thoughts from y'all?

* * *

In our full conversation, we circled around a couple of questions--approaching them from different angles and debating meanings. One central facet of our discussion was whether any of the characters are sympathetic. Our son responded with frustration to the question, "Everybody and nobody! That is such a complex question that I don't know how you could expect a straight answer."

While he has a point, we weren't about to let the issue rest. We agreed that Tom Buchanan was the least sympathetic. David suggested that our condemnation of Tom might be greater now than it was when Fitzgerald was writing the book in the mid-1920s. Eugenic thought and Jim Crow racism were the background to his perspectives and his attitudes might have seemed more acceptable then. Our son A. pointed out that the other characters did not seem to accept Tom's views as normal at all. I was torn; Daisy and Nick simply laugh at Tom's ideas--not explicitly reject them or seem disturbed by their implications.

Daisy starts at the beginning of the book as a mostly sympathetic character. We are hopeful that she will find true love in the book and escape from evil Tom. By the end, however, our opinion of her has changed. She seems self-centered, blind to other people's needs, and shallow.

Is Gatsby the character with whom we are to identify? That seems impossible. He is distant at the beginning, drawn larger than life in the middle (perhaps deserving the superhero title of "The Great Gatsby"), and committed to goals we don't respect. On the other hand, Nick (the narrator) tells us that Gatsby is worth far more than the "whole damn bunch" of Toms and Daisys and their ilk. His hope for the future seem to be what the narrator admires--but it is this commitment to building his future that encourages Gatsby to lie about his past and engage in illegal or unethical acts in order to make that dream come true.

My family came to no conclusions beyond what A. suggested at the beginning: that the characters all embody both good and bad--and in the process gain both our sympathy and our contempt.

The lesson Fitzgerald appears to be telling us is that the wealth and the quest for more wealth leads to spiritual or ethical ruin. Although the author seems to say that reaching for a dream is a noble goal, reaching for the American dream--that is, in this book, the search for unbridled wealth--is fundamentally destructive. Tom and Daisy, divorced from any higher goals of humanity and immersed in a fishbowl of money, "smashed up things and creatures then retreated back into their money, or their vast carelessness, or whatever it was that kept them together, and let other people clean up the mess they had made." Nick ends the book by realizing that he must leave the glittering disconnection of New York. He decides to move back to his Midwestern home--a land of honesty and plainness, a place where people take responsibility for the harm they cause.

But is the corruptive power of the high life what Fitzgerald meant for us to see in this book? The first-person narration makes it easy for us to conflate the character of Nick with Fitzgerald. But the author's real similarity is not with Nick. The better fit is Gatsby. Like the character of Gatsby, Fitzgerald grew up poor, fell in love with a rich girl who would not marry him for monetary reasons, and eventually made money enough to allow him to get the girl. Fitzgerald and his wife Zelda watched their lives spiral more and more out of control in the years after the publication of The Great Gatsby. Their lives became as explosive as Gatsby's.

Interestingly, Nick idealizes Gatsby even as he rejects much of what defines him. Perhaps this book was Fitzgerald's attempt to analyze both the dangers and the magic of the life he had chosen to embrace.

No comments:

Post a Comment